We Remember

1945-1946

1945-1946

BYPASSED AT GUAM?

Graeme Robinson Vol. II, p. 120

After returning to Guam from Truk, we swung around the mooring buoy for a couple of days, doing nothing. Other ships were getting their orders for occupation duty, but we got silence. We were still the flagship for Commander, Marianas.

About 1:30 A M I received a call from the CWO that we had received a visual message from the Port Director to send an officer messenger for "coded dispatch."

The captain sent me in his new skimmer. Upon return I found the code room loaded with nosey "C" Division officers. I got rid of them and locked the door. The first thing I found was that the message was in a "strip" cipher, a very low security code. On decoding, I found it was directed to a CTU 58.3.5 (or something like that.) I called out to Lt. Herzberg to start digging out all traffic addressed to that CTU as neither of us had ever heard of it and I was afraid we had missed something, a definite No No for a Communications Officer. The message directed us to send two destroyers to some island to pick up something and return to Tinian. This made no sense to me.

By now it was about 5:00 AM and I broke out the Captain, asking if he knew anything about these orders. He also had no idea, and called the signal bridge to tell the Port Director to have a car at the dock at 0700 for "personal representative of the Commanding Officer, Portland." That was to be me.

A quick shower and clean uniform was about all I had time for before leaving. Sure enough, there was a big white Chrysler waiting docked, and away we went. Going into Island Command Headquarters, I passed through Operations. The first officer I saw was Captain Naquin, acting Chief of Staff for the Truk surrender. He looked up in surprise at my puzzled and frazzled look, and I showed him the message we had been working on all night. He laughed and with some snide comment about JCC (Joint Communications Center) he pulled out his file and handed me his copy of the message we should have received It said:

"USS Portland, hereby detached, proceed via points xray and zulu to Pearl to join TF 11 for further transfer to CincLant for Navy Day operations."

Needless to say, my expression changed. All the way back to the ship, that copy burned a hole in my shirt pocket. The next day we flew the 997 foot "Homeward Bound" pennant and headed for home. Without getting that message cleared up, who knows, we might still be wearing out swivel hooks in Apra harbor!!

NIGHT LIGHTS - A LETTER HOME

Barney Kliks

Sept. 10, 1945

Dear Folks,

"Scuttlebutt" is flying thick and fast. The best seems to point to return to the States sometime soon. It seems incredible that I may get back home, meaning "the States." I can tell you that when I left Frisco, I had a very strong premonition that I'd never return. When I got out in these waters and left the liberty ship for the Fighting "P," my premonition was confirmed into what was a certainty.

Many others shared it, for this ship has had so many close shaves, her hick was up. She was lightly armored (in comparison to the newer Heavies and Light cruisers) and lightly armed against enemy aircraft. You can see what a "tin fish" or two did to the Indianapolis...tore her bottom out and down in less than 15 minutes.

Even now, I can't believe it. Out here, half a world away, up at all hours of the night, with the noises and strains of war, it did not occur to me that it would end and we would be back.

Well now with the noise, the concussions, the horrible flames and death dealing explosions, the midnight "General Alarms", the diving planes, etc. fading away and the night actually punctuated with lights, Tm beginning to realize I will have a life to live with my family.

It is so startling to come up here on night watches and see lights over the harbor. We even broke out clearance lights and anchor buoy lights for the safety of other ships. You have no idea how wonderful it is to see lights.

I was covered with what we call "ladder Shankers"~bruises and cuts from steel ladders and "knife edges" (raised curbs between each water-tight compartment) from miming to G.Q. station half-dressed and half asleep in the blackness. My room was "Torpedo Junction"...on the waterline, far forward in the bow between the aviation gas, bombs, the paint locker and forward of the 8" magazine.

One night we heard a thud and an explosion. A torpedo had hit us at an angle, smashed a frame and bent the hull in the Marine compartment, but had glanced off and exploded at the end of its run. It must have been fired at too close a range. And then the guns started firing...air raid to boot.

I got to my battle station all right, only to find planes coming in. One snooper had dropped flares silhouetting us and blinding us - making us sitting ducks for the sub. Thank God for Capt. Settle - he had us full speed and in tight circles. A bomb missed as and I saw a plane dive, full of holes, falling into the sea about 100 yards on our starboard bow. By the time I told another fellow to put on his helmet and flash gear and see it burn on the water, it was on our port quarter - the ship had turned that quickly.

Many other ships - too many - were not that lucky. On the 12th of April it was terrible and I saw in 10 minutes (probably only 4) all of the war I needed for a lifetime.

Well - enough of that - too much, in fact. But that is hard to get out of your mind and I cannot yet realize that it is finally over.

Barney Kliks

Sept. 10, 1945

Dear Folks,

"Scuttlebutt" is flying thick and fast. The best seems to point to return to the States sometime soon. It seems incredible that I may get back home, meaning "the States." I can tell you that when I left Frisco, I had a very strong premonition that I'd never return. When I got out in these waters and left the liberty ship for the Fighting "P," my premonition was confirmed into what was a certainty.

Many others shared it, for this ship has had so many close shaves, her hick was up. She was lightly armored (in comparison to the newer Heavies and Light cruisers) and lightly armed against enemy aircraft. You can see what a "tin fish" or two did to the Indianapolis...tore her bottom out and down in less than 15 minutes.

Even now, I can't believe it. Out here, half a world away, up at all hours of the night, with the noises and strains of war, it did not occur to me that it would end and we would be back.

Well now with the noise, the concussions, the horrible flames and death dealing explosions, the midnight "General Alarms", the diving planes, etc. fading away and the night actually punctuated with lights, Tm beginning to realize I will have a life to live with my family.

It is so startling to come up here on night watches and see lights over the harbor. We even broke out clearance lights and anchor buoy lights for the safety of other ships. You have no idea how wonderful it is to see lights.

I was covered with what we call "ladder Shankers"~bruises and cuts from steel ladders and "knife edges" (raised curbs between each water-tight compartment) from miming to G.Q. station half-dressed and half asleep in the blackness. My room was "Torpedo Junction"...on the waterline, far forward in the bow between the aviation gas, bombs, the paint locker and forward of the 8" magazine.

One night we heard a thud and an explosion. A torpedo had hit us at an angle, smashed a frame and bent the hull in the Marine compartment, but had glanced off and exploded at the end of its run. It must have been fired at too close a range. And then the guns started firing...air raid to boot.

I got to my battle station all right, only to find planes coming in. One snooper had dropped flares silhouetting us and blinding us - making us sitting ducks for the sub. Thank God for Capt. Settle - he had us full speed and in tight circles. A bomb missed as and I saw a plane dive, full of holes, falling into the sea about 100 yards on our starboard bow. By the time I told another fellow to put on his helmet and flash gear and see it burn on the water, it was on our port quarter - the ship had turned that quickly.

Many other ships - too many - were not that lucky. On the 12th of April it was terrible and I saw in 10 minutes (probably only 4) all of the war I needed for a lifetime.

Well - enough of that - too much, in fact. But that is hard to get out of your mind and I cannot yet realize that it is finally over.

FANS AND SALT WATER SPRAY

George Loock

As I recall, one of the tasks that kept the Electrician's Mates busy was repairing fans. When these fans were ostensibly beyond repair, we would order replacements fi-om the local supply depot. It seemed to me, however, that our EMs seldom junked the old fans. Instead, they rewound the armatures, dressed the commutators, and made any other repairs to render the fans reusable.

In time, we had such a glut of fans that almost every self-respecting "E"Div. sailor had a personally repaired fan by his bunk. No one seemed to object - witness the lack of extreme criticism during those lower deck inspections.

Hank Dieterich and I shared a cabin on the Main Deck, Port side. After the war and we were headed back to the States, there was no further "darken ship requirement" when cruising at night. It was a pretty and welcome sight to see all of the ships displaying running lights after years of "darken ship."

As we steamed southeast towards Panama, the weather got warmer and warmer. Hank and I scrounged around a found a wind scoop that fit through the cabin porthole to draw fresh air into the cabin. This arrangement worked great until the ship entered the Japanese Current, with swells now crossing the bow from port to starboard.

One night while Hank was sleep in the upper bunk and I was reading in the lower one, a huge wave slapped the port side just forward of our cabin. The plume of spray that erupted was quickly grabbed by our wonderful air scoop and in a flash we both were soaked to the skin. To this day, I don’t remember how we got the bedding dry. Perhaps the Steward's Mate obtained permission to air bedding the next day.

George Loock

As I recall, one of the tasks that kept the Electrician's Mates busy was repairing fans. When these fans were ostensibly beyond repair, we would order replacements fi-om the local supply depot. It seemed to me, however, that our EMs seldom junked the old fans. Instead, they rewound the armatures, dressed the commutators, and made any other repairs to render the fans reusable.

In time, we had such a glut of fans that almost every self-respecting "E"Div. sailor had a personally repaired fan by his bunk. No one seemed to object - witness the lack of extreme criticism during those lower deck inspections.

Hank Dieterich and I shared a cabin on the Main Deck, Port side. After the war and we were headed back to the States, there was no further "darken ship requirement" when cruising at night. It was a pretty and welcome sight to see all of the ships displaying running lights after years of "darken ship."

As we steamed southeast towards Panama, the weather got warmer and warmer. Hank and I scrounged around a found a wind scoop that fit through the cabin porthole to draw fresh air into the cabin. This arrangement worked great until the ship entered the Japanese Current, with swells now crossing the bow from port to starboard.

One night while Hank was sleep in the upper bunk and I was reading in the lower one, a huge wave slapped the port side just forward of our cabin. The plume of spray that erupted was quickly grabbed by our wonderful air scoop and in a flash we both were soaked to the skin. To this day, I don’t remember how we got the bedding dry. Perhaps the Steward's Mate obtained permission to air bedding the next day.

NAVIGATING TO EUROPE

H. F. "Buddy" Fountain

I can easily recall when the new skipper and the navigator, Cdr. Jackson, called me into the wardroom and asked me if we could take the ship to Europe. In the then recent times, before the war was over, Chief QM Sands, QM2c Wilcox and I had been assisting the navigator. Sands and Wilcox were no longer aboard and no one else had ever been to Europe. I felt confident that we could navigate to Europe and I told them both so. What I did not know was that the North Atlantic is a different ball game than the Pacific.

The first day we got a "sun line" and that night a couple of "star shots." They were the last sights we got. As some of you know, it's always rough in the North Atlantic and at this time of year it was totally overcast. After three or four days advancing the "lines" we had the first day, we were concerned. We knew "about" where we were but that is not good enough for traveling alone to Europe.

Now, this is an unbelievable story. Sometime in 1944 when we were in Pearl Harbor, we went to LORAN school for a three day "crash course." The ship sent Cdr. Jackson, Chief Sands, Chief Radioman Donato and myself. LORAN was new at the time and they only gave us three days to learn Theory, Calibration and the Sets and Charts for navigation. (This form of navigation is completely different from Celestial navigation which we had been using.)

After the course, we forgot all about it since there were no stations for us to use. (Our only station was at Pearl.) Our course sets just laid in the chart house collecting dust. With no sun, moon or stars available due to the weather, we had no choice but to dig out those old manuals, read and refresh our three day course and start to navigate by LORAN.

Chief Donato came up and calibrated our set. Of course, the east coast had stations all over the place, as did Newfoundland, the Azores, England, etc.

Our goal was a 17 mile light at Plymouth, England. Believe it or not, we missed the light by fifteen minutes. We were "set" to the south, (tides) and after we turned left for 15 minutes the light appeared. The new Skipper could not believe it and I was a little surprised myself.

From Plymouth, England, where we refueled and picked up mail, we went through the English Channel to Le Havre, France, for the troops. At that time the mine sweepers were cutting mines loose, and it was quite an experience, with live mines floating all over the place.

Those two trips to France will long be remembered by the Portland crew members who were aboard during this time.

TO EUROPE ON A THREE DAY COURSE

H. F. "Buddy" Fountain Vol. II, pp. 121-122

During the war, on one of our rare trips back to Pearl Harbor, the Portland sent four of us to a three day school for LORAN which was, at that time, a new method for navigation. Commander Jackson, the navigator. Chief Quartermaster Sands, Chief Electrician's Mate Donato and myself were the four.

The course was a three day "crash" course that included the theory, calibration of the sets and navigation with new type of charts. Of course, this method of navigation is totally different from celestial navigation that the navigator and quartermasters were familiar with. While in Pearl we had the new Loran sets installed.

After our short stay in Pearl, we were off again to the battleground of the Pacific. Since the Japs held all the territory in the South Pacific, there were no Loran stations sending signals, which meant that we never used this new fangled method of navigation. In fact we never gave it a thought on the bridge. The set stood in the corner of the chart house and was never turned on.

After the war we came around to the east coast and were given orders to go to Europe and pick up troops and return. By this time Chief Sands had mustered out with points and we had a new skipper. (We had cut down to a "skeleton" crew.)

One day I had a call to report to the Captain's cabin. Commander Jackson and the new skipper (I believe he was Lyman Thackery) asked me if I thought we could get the ship to Europe. (I understood that not a single line officer on the ship had ever been on a ship across the Atlantic.) Having a good background from Quartermasters school and two years on the bridge with three different navigators, I felt confident and said "Sure." What I did not know was that the North Atlantic is always rough and most of the time overcast.

The first day out we got a "sun line" and that night two or three star shots. After that we could not see anything but clouds. Of course, we were traveling alone and using our tracking system chart which ran off the Gyro compass and pit log that was giving us an approximate position. We were steering the correct course for our destination, but had no idea how much we were being "set" to the north or south.

After about three days of such travel, all in the chart house were becoming quite concerned about our predicament. Still no sights from the sun, moon or stars. We knew "about" where we were, but that was about it. I told the navigator that we had better dig out our instructional manual on Loran and call Chief Donato to come up and calibrate the equipment, since that was all we had.

There were Loran stations all over the Atlantic coast, Newfoundland, the Azores, England and Europe. We began navigating with Loran.

Our point of landfall was at Seventeen Mile Light at Land's End, England. We were supposed to see that light just before dark on the seventh day, about fifteen minutes before dark Of course, a good half hour before dark all eyes were on the bridge and all lookouts were peeling their eyes forward looking for that light.

The skipper was asking everyone on the bridge what they thought. I had been studying the tide charts the past couple of days and told the skipper and navigator that I thought we were set to the south.

We changed course about fifteen degrees to the left and in about fifteen minutes the beautiful Land's End Light started beaming our way. WOW! was I elated. So was everyone else on the bridge. Then I silently laughed to myself, thinking "Isn't that something. To get a ship to Europe on a three-day crash course?"

H. F. "Buddy" Fountain Vol. II, pp. 121-122

During the war, on one of our rare trips back to Pearl Harbor, the Portland sent four of us to a three day school for LORAN which was, at that time, a new method for navigation. Commander Jackson, the navigator. Chief Quartermaster Sands, Chief Electrician's Mate Donato and myself were the four.

The course was a three day "crash" course that included the theory, calibration of the sets and navigation with new type of charts. Of course, this method of navigation is totally different from celestial navigation that the navigator and quartermasters were familiar with. While in Pearl we had the new Loran sets installed.

After our short stay in Pearl, we were off again to the battleground of the Pacific. Since the Japs held all the territory in the South Pacific, there were no Loran stations sending signals, which meant that we never used this new fangled method of navigation. In fact we never gave it a thought on the bridge. The set stood in the corner of the chart house and was never turned on.

After the war we came around to the east coast and were given orders to go to Europe and pick up troops and return. By this time Chief Sands had mustered out with points and we had a new skipper. (We had cut down to a "skeleton" crew.)

One day I had a call to report to the Captain's cabin. Commander Jackson and the new skipper (I believe he was Lyman Thackery) asked me if I thought we could get the ship to Europe. (I understood that not a single line officer on the ship had ever been on a ship across the Atlantic.) Having a good background from Quartermasters school and two years on the bridge with three different navigators, I felt confident and said "Sure." What I did not know was that the North Atlantic is always rough and most of the time overcast.

The first day out we got a "sun line" and that night two or three star shots. After that we could not see anything but clouds. Of course, we were traveling alone and using our tracking system chart which ran off the Gyro compass and pit log that was giving us an approximate position. We were steering the correct course for our destination, but had no idea how much we were being "set" to the north or south.

After about three days of such travel, all in the chart house were becoming quite concerned about our predicament. Still no sights from the sun, moon or stars. We knew "about" where we were, but that was about it. I told the navigator that we had better dig out our instructional manual on Loran and call Chief Donato to come up and calibrate the equipment, since that was all we had.

There were Loran stations all over the Atlantic coast, Newfoundland, the Azores, England and Europe. We began navigating with Loran.

Our point of landfall was at Seventeen Mile Light at Land's End, England. We were supposed to see that light just before dark on the seventh day, about fifteen minutes before dark Of course, a good half hour before dark all eyes were on the bridge and all lookouts were peeling their eyes forward looking for that light.

The skipper was asking everyone on the bridge what they thought. I had been studying the tide charts the past couple of days and told the skipper and navigator that I thought we were set to the south.

We changed course about fifteen degrees to the left and in about fifteen minutes the beautiful Land's End Light started beaming our way. WOW! was I elated. So was everyone else on the bridge. Then I silently laughed to myself, thinking "Isn't that something. To get a ship to Europe on a three-day crash course?"

"THIS ONE'S ON ME"

Barney Kliks Vol. II, pp. 122-123

After our first trip to Le Havre we had a few days in NYC before starting on the ill-fated last cruise.

A member of the Navy League posted a notice of activities for all members of the ship's crew. One of them struck my fancy; the great Guy Lombardo with his entire orchestra was going to be at the finest hotel in Philadelphia for a dinner dance.

I got Lieutenant Bill Collinson to join me and reserve two places for dinner that night. We had a long walk through the Navy Yard area, a very bad section of town, and we packed our 45s. At the edge of town the Navy had a Shore Patrol station where we checked our guns, then got on a streetcar into town.

We were seated at a nice table and Guy Lombardo had already started playing The Navy League hostess asked us if we had dates or were we alone? When we told her we were alone, she said "Would you mind if I had a couple of our ladies join you at the table for conversation?" etc. Collinson said "Sure." (With his great southern hospitality.)

(He, too was a lawyer and after the war became a well known Senior Judge in the Federal Court of Appeals.)

Presently a couple of nicely dressed ladies, in their 30's I suppose, came over and sat down with us and started a conversation. Of course, we bought them drinks, and then we had to order dinner, which was at some phenomenal price, even in those days!

The music was marvelous and relaxing. I had just come off a long watch and was very tired. I kept dozing off". Finally, I fell fast asleep. I woke up probably an hour or two later. The two ladies were giggling and told me that Lt. Collinson excused himself earlier saying he had to go on watch and had to be at the ship on duty in an hour (which was BS.)

We had had a fine dinner and drinks. That combination put me to sleep easily.

Having to be an "officer and a gentleman," I knew it was up to me to see that they got home. I found out that neither resided close by. In fact one was way north, and the other clear south of the city. They told me the buses did not run this late, and it would be dangerous to take public transportation anyway! I therefore had to order two cabs to get the ladies home. I then proceeded to walk a long distance back to retrieve my gun, through the Navy Yard and back to the ship.

Barney Kliks Vol. II, pp. 122-123

After our first trip to Le Havre we had a few days in NYC before starting on the ill-fated last cruise.

A member of the Navy League posted a notice of activities for all members of the ship's crew. One of them struck my fancy; the great Guy Lombardo with his entire orchestra was going to be at the finest hotel in Philadelphia for a dinner dance.

I got Lieutenant Bill Collinson to join me and reserve two places for dinner that night. We had a long walk through the Navy Yard area, a very bad section of town, and we packed our 45s. At the edge of town the Navy had a Shore Patrol station where we checked our guns, then got on a streetcar into town.

We were seated at a nice table and Guy Lombardo had already started playing The Navy League hostess asked us if we had dates or were we alone? When we told her we were alone, she said "Would you mind if I had a couple of our ladies join you at the table for conversation?" etc. Collinson said "Sure." (With his great southern hospitality.)

(He, too was a lawyer and after the war became a well known Senior Judge in the Federal Court of Appeals.)

Presently a couple of nicely dressed ladies, in their 30's I suppose, came over and sat down with us and started a conversation. Of course, we bought them drinks, and then we had to order dinner, which was at some phenomenal price, even in those days!

The music was marvelous and relaxing. I had just come off a long watch and was very tired. I kept dozing off". Finally, I fell fast asleep. I woke up probably an hour or two later. The two ladies were giggling and told me that Lt. Collinson excused himself earlier saying he had to go on watch and had to be at the ship on duty in an hour (which was BS.)

We had had a fine dinner and drinks. That combination put me to sleep easily.

Having to be an "officer and a gentleman," I knew it was up to me to see that they got home. I found out that neither resided close by. In fact one was way north, and the other clear south of the city. They told me the buses did not run this late, and it would be dangerous to take public transportation anyway! I therefore had to order two cabs to get the ladies home. I then proceeded to walk a long distance back to retrieve my gun, through the Navy Yard and back to the ship.

CRAP GAMES

Don Martin

It was no wonder that Buddy Fountain, QM2c, almost had us headed for South America instead of Le Havre, France, because there was always a rumor on the signal bridge that he and Jack Utz, QM2c and Lloyd Wilcox, QM2c, were somehow draining the "juice" out of the gyro compass. Of course they had to get in line behind CQM Sands. We were probably lucky to find the 17 mile light at Plymouth, England, and not end up in Rio De Janeiro.

When we picked up the troops at Le Havre and got underway, it did not take long for the 250 of us crew members to see that we had a bunch of soldiers aboard with more money than most of us had ever seen. In less than 24 hours there were crap games going on all over the ship. The soldiers wanted the sailors to run the games and cut "acey-deucy."

From a deck of cards they wanted the 4-5-6-8-9 & 10 pulled and when one of them rolled for his point, they wanted that numbered card on the deck so there would be no arguments. If the shooter rolled snake eyes or ace-deuce, the sailor got to cut the shooter's bet, not the one or more who faded him.

It so happened that a large number of these troops were from a quartermaster outfit. Unlike our quartermasters, they handled Army supplies. Most of this bunch said they had made thousands of dollars from black-marketing everything from smokes to Jeeps. All of the money was "gold-seal" currency but it spent just as good as green shield.

On the second day out of Le Havre, Al Clark, BM2c, 5th Div., who manned the starboard whaleboat and sometimes wore a Colt 45 as assistant Master at Arms with the job of holding down cheating in the chow lines, and I, got our heads together and decided to form a partnership to run the crap game.

There was only one problem - dice were as scarce as a scratch on the keel. We finally located a pair of twenty-five cent white dice and paid $35 for them. That evening Al got a piece of 2" x 4" from the carpenter shop and we spread a blanket out on the deck in #2 mess hall, placed the 2x4 against the bulkhead and we were in business.

Never in our lives had we seen such wild gambling. Sometimes Al would handle the dice and I would take care of the card indicating the point, and vice versa. The soldiers insisted that the dice hit the bulkhead so as to eliminate any sharpie who could "slide" the dice. After 4 or 5 hours one of the officers or the MA broke up the game. Al and I went to his compartment and counted our money. We split over $600 that we had cut from the game and felt rich.

Some of you may recall the soldier that had so much money and the crew member from the "C" division who sold his bunk for $500.00.

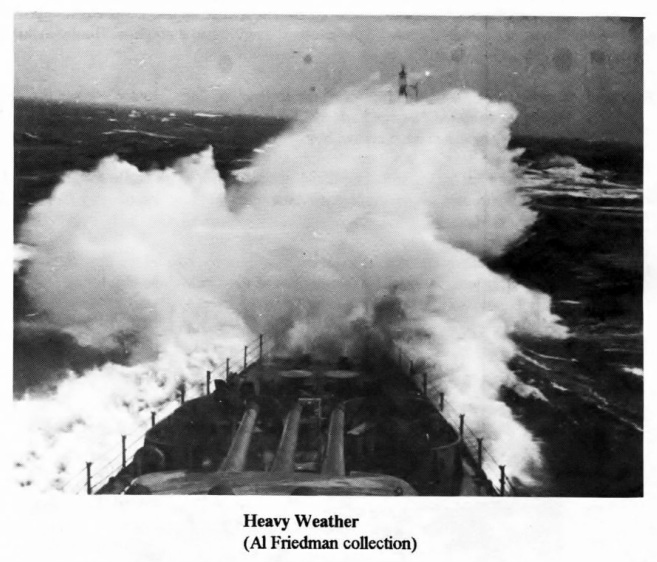

The rest of that trip is history. When that 100 foot wave hit us that dark night, I was on the port side of the signal bridge holding on to the shield. I do remember looking straight down into the phosphorous water and saying "Please, God, let us roll back."

Don Martin

It was no wonder that Buddy Fountain, QM2c, almost had us headed for South America instead of Le Havre, France, because there was always a rumor on the signal bridge that he and Jack Utz, QM2c and Lloyd Wilcox, QM2c, were somehow draining the "juice" out of the gyro compass. Of course they had to get in line behind CQM Sands. We were probably lucky to find the 17 mile light at Plymouth, England, and not end up in Rio De Janeiro.

When we picked up the troops at Le Havre and got underway, it did not take long for the 250 of us crew members to see that we had a bunch of soldiers aboard with more money than most of us had ever seen. In less than 24 hours there were crap games going on all over the ship. The soldiers wanted the sailors to run the games and cut "acey-deucy."

From a deck of cards they wanted the 4-5-6-8-9 & 10 pulled and when one of them rolled for his point, they wanted that numbered card on the deck so there would be no arguments. If the shooter rolled snake eyes or ace-deuce, the sailor got to cut the shooter's bet, not the one or more who faded him.

It so happened that a large number of these troops were from a quartermaster outfit. Unlike our quartermasters, they handled Army supplies. Most of this bunch said they had made thousands of dollars from black-marketing everything from smokes to Jeeps. All of the money was "gold-seal" currency but it spent just as good as green shield.

On the second day out of Le Havre, Al Clark, BM2c, 5th Div., who manned the starboard whaleboat and sometimes wore a Colt 45 as assistant Master at Arms with the job of holding down cheating in the chow lines, and I, got our heads together and decided to form a partnership to run the crap game.

There was only one problem - dice were as scarce as a scratch on the keel. We finally located a pair of twenty-five cent white dice and paid $35 for them. That evening Al got a piece of 2" x 4" from the carpenter shop and we spread a blanket out on the deck in #2 mess hall, placed the 2x4 against the bulkhead and we were in business.

Never in our lives had we seen such wild gambling. Sometimes Al would handle the dice and I would take care of the card indicating the point, and vice versa. The soldiers insisted that the dice hit the bulkhead so as to eliminate any sharpie who could "slide" the dice. After 4 or 5 hours one of the officers or the MA broke up the game. Al and I went to his compartment and counted our money. We split over $600 that we had cut from the game and felt rich.

Some of you may recall the soldier that had so much money and the crew member from the "C" division who sold his bunk for $500.00.

The rest of that trip is history. When that 100 foot wave hit us that dark night, I was on the port side of the signal bridge holding on to the shield. I do remember looking straight down into the phosphorous water and saying "Please, God, let us roll back."

THE THINGS YOU DO FOR MONEY

Robert Braswell

Yes, I sold my bunk. I’m probably not the only one, but on our trip back from France I sold it to a G.I. I don’t remember what I got for it, but I’m sure it was not cheap because he was loaded with money. And that was only part of the story.

He must have had his duffle bag full of cash. It had two combination locks on it and he kept a German Luger tucked in his waist. Not only did I sell him my bunk, but he also had more problems which did not take me long to offer solutions for. He would not leave his duffle bag even though he had to go chow and to the head. I made a deal to bring him his chow at $20 a meal. I also took his Luger and guarded his duffle bag when he went to the head.

After several days out and we got into the big storm, he got suspicious as too many sailors were hanging around his (my) bunk. We solved that by my getting a scrub bucket (for which he paid plenty.) I would take it to the head, empty it and wash it out so he never had to leave the bunk area. This was a little more of a dirty job than just getting his chow, so this cost him $25 per trip.

After we left the Azores and got closer to New York, he looked awful as he had not showered or shaved in 12-14 days. We had become pretty good friends during the trip and upon leaving the ship with his duffle bag over his shoulder, his Luger tucked in his waist, we shook hands, he thanked me, handed me several hundred dollars and down the gang plank he went.

The next day, I went ashore and sent home a money order for about $4,000. This was more money than I had made during my 4 years in the Navy. I bought a new car with part of the money when I was discharged and enjoyed every mile of it.

Incidentally, the G.I. had been in the division known as the "Red Ball Express" carrying supplies to the front lines.

Robert Braswell

Yes, I sold my bunk. I’m probably not the only one, but on our trip back from France I sold it to a G.I. I don’t remember what I got for it, but I’m sure it was not cheap because he was loaded with money. And that was only part of the story.

He must have had his duffle bag full of cash. It had two combination locks on it and he kept a German Luger tucked in his waist. Not only did I sell him my bunk, but he also had more problems which did not take me long to offer solutions for. He would not leave his duffle bag even though he had to go chow and to the head. I made a deal to bring him his chow at $20 a meal. I also took his Luger and guarded his duffle bag when he went to the head.

After several days out and we got into the big storm, he got suspicious as too many sailors were hanging around his (my) bunk. We solved that by my getting a scrub bucket (for which he paid plenty.) I would take it to the head, empty it and wash it out so he never had to leave the bunk area. This was a little more of a dirty job than just getting his chow, so this cost him $25 per trip.

After we left the Azores and got closer to New York, he looked awful as he had not showered or shaved in 12-14 days. We had become pretty good friends during the trip and upon leaving the ship with his duffle bag over his shoulder, his Luger tucked in his waist, we shook hands, he thanked me, handed me several hundred dollars and down the gang plank he went.

The next day, I went ashore and sent home a money order for about $4,000. This was more money than I had made during my 4 years in the Navy. I bought a new car with part of the money when I was discharged and enjoyed every mile of it.

Incidentally, the G.I. had been in the division known as the "Red Ball Express" carrying supplies to the front lines.

"CAN YOU HEAR ME OUT THERE?"

Albert "Abe" Boman Vol. II, pp. 123-124

I have a couple of pictures taken during the Atlantic hurricane in December of 1945. One shows the starboard whaleboat which had been torn loose and was swinging wildly. The deck crew managed to get it under control and lashed down on the deck. One of the davits appears to be gone and the other is severely twisted. (Next morning the boat was completely gone.) In the other picture you can see the starboard hangar door that was smashed, the Stokes baskets on the hangar bulkhead and fire hoses can be seen and the ladder to the hangar deck is hanging at a 45 degree angle. On the right side is the 500 kilocycle emergency flat-top antenna from Radio III which we never got fired up.

We tried desperately to contact NSS in Washington on the TBK-9. I spent the night running from the transmitter to it's whip antenna on the after stack wiping off and drying it's insulator, then back to the transmitter to load the antenna. I'd just get it loaded and it would be shorted out again. The plate of the final amplifier's normal temperature was cherry red. I had it cranked up to white hot and kept blowing the overload. Burned out one 860 tube that night. We did manage to reach NSS after about five hours of this merry-go-round. Quite exciting up on the after stack when you're rolling 45 degrees.

I recall going into Le Havre and the harbor master kept calling. I had us set up on the TDQ and he obviously wasn't receiving us. Warrant Officer Nicholas came stomping back to Radio II, looked at the nameplate reading of the transmitter and offered "No wonder - this oversized popcorn popper can't get beyond the forecastle." We set up the TBM-7 and probably blew the 1st stage of the harbor master's receiver.

On our way to the Azores, after things calmed down, Nicholas and I dug out an old speed key from one of our storage rooms. He had made up a message and all who wanted to let the folks at home know we were safe, could send a telegram. I don't know how many hours that man sat at that key tapping out names and addresses.

At one point I made my way up to Radio I while we were pitching and rolling. Those poor guys trying to copy signals. One time they'd be glued to their chairs and the next moment, on the down pitch, they'd be weightless and lifted off their chairs. The sea cabin being one deck above Radio I - I can just imagine what they were going through. And the poor troops - I've seen pay lines and chow lines, but never lines to the head to up-chuck. Once a guy got to the head of the line he was very reluctant to give it up.

Here is a poem written by one of the passengers on that miserable trip:

We told you seven but it took fifteen.

The weather was rough and mostly mean.

All through the night the great ship did pitch,

you in your sack did nothing but bitch.

You cussed her in and you cussed her out,

but she sailed on with a heart so stout.

Call her the Portland or even Sweet Pea,

she's doing her job and asks no fee.

To all GI's with happiness in hearts,

remember, t'was the Portland who gave to it's start.

By K . C. Konis

S. T. O.

Albert "Abe" Boman Vol. II, pp. 123-124

I have a couple of pictures taken during the Atlantic hurricane in December of 1945. One shows the starboard whaleboat which had been torn loose and was swinging wildly. The deck crew managed to get it under control and lashed down on the deck. One of the davits appears to be gone and the other is severely twisted. (Next morning the boat was completely gone.) In the other picture you can see the starboard hangar door that was smashed, the Stokes baskets on the hangar bulkhead and fire hoses can be seen and the ladder to the hangar deck is hanging at a 45 degree angle. On the right side is the 500 kilocycle emergency flat-top antenna from Radio III which we never got fired up.

We tried desperately to contact NSS in Washington on the TBK-9. I spent the night running from the transmitter to it's whip antenna on the after stack wiping off and drying it's insulator, then back to the transmitter to load the antenna. I'd just get it loaded and it would be shorted out again. The plate of the final amplifier's normal temperature was cherry red. I had it cranked up to white hot and kept blowing the overload. Burned out one 860 tube that night. We did manage to reach NSS after about five hours of this merry-go-round. Quite exciting up on the after stack when you're rolling 45 degrees.

I recall going into Le Havre and the harbor master kept calling. I had us set up on the TDQ and he obviously wasn't receiving us. Warrant Officer Nicholas came stomping back to Radio II, looked at the nameplate reading of the transmitter and offered "No wonder - this oversized popcorn popper can't get beyond the forecastle." We set up the TBM-7 and probably blew the 1st stage of the harbor master's receiver.

On our way to the Azores, after things calmed down, Nicholas and I dug out an old speed key from one of our storage rooms. He had made up a message and all who wanted to let the folks at home know we were safe, could send a telegram. I don't know how many hours that man sat at that key tapping out names and addresses.

At one point I made my way up to Radio I while we were pitching and rolling. Those poor guys trying to copy signals. One time they'd be glued to their chairs and the next moment, on the down pitch, they'd be weightless and lifted off their chairs. The sea cabin being one deck above Radio I - I can just imagine what they were going through. And the poor troops - I've seen pay lines and chow lines, but never lines to the head to up-chuck. Once a guy got to the head of the line he was very reluctant to give it up.

Here is a poem written by one of the passengers on that miserable trip:

We told you seven but it took fifteen.

The weather was rough and mostly mean.

All through the night the great ship did pitch,

you in your sack did nothing but bitch.

You cussed her in and you cussed her out,

but she sailed on with a heart so stout.

Call her the Portland or even Sweet Pea,

she's doing her job and asks no fee.

To all GI's with happiness in hearts,

remember, t'was the Portland who gave to it's start.

By K . C. Konis

S. T. O.

FREE TIME

Bob Touhey Vol. II, p. 122

During the Atlantic hurricane in December, 1945, I remember waking up after a deep sleep filled with dreams about submerging to avoid the storm because the rumor going around the previous evening was "The skipper was formerly assigned to submarines."

On arriving at the entrance to my duty station (one of the firerooms) I noticed a large hose stuck down the hatch and a seaman who had a re-breather mask on his face and the attaching chemical container fastened to his chest. I thought a fire had occurred at my workplace, but the man with the mask, upon removing it, told me I couldn't report to duty due to the flooded condition of the compartment. So - I spent the remainder of the week, until we docked in New York City, walking topside and watching the activities of the repair details and the beauty of the Azores islands.

Bob Touhey Vol. II, p. 122

During the Atlantic hurricane in December, 1945, I remember waking up after a deep sleep filled with dreams about submerging to avoid the storm because the rumor going around the previous evening was "The skipper was formerly assigned to submarines."

On arriving at the entrance to my duty station (one of the firerooms) I noticed a large hose stuck down the hatch and a seaman who had a re-breather mask on his face and the attaching chemical container fastened to his chest. I thought a fire had occurred at my workplace, but the man with the mask, upon removing it, told me I couldn't report to duty due to the flooded condition of the compartment. So - I spent the remainder of the week, until we docked in New York City, walking topside and watching the activities of the repair details and the beauty of the Azores islands.

ATLANTIC HURRICANE

Herman Ferguson Vol. II, pp. 127-128

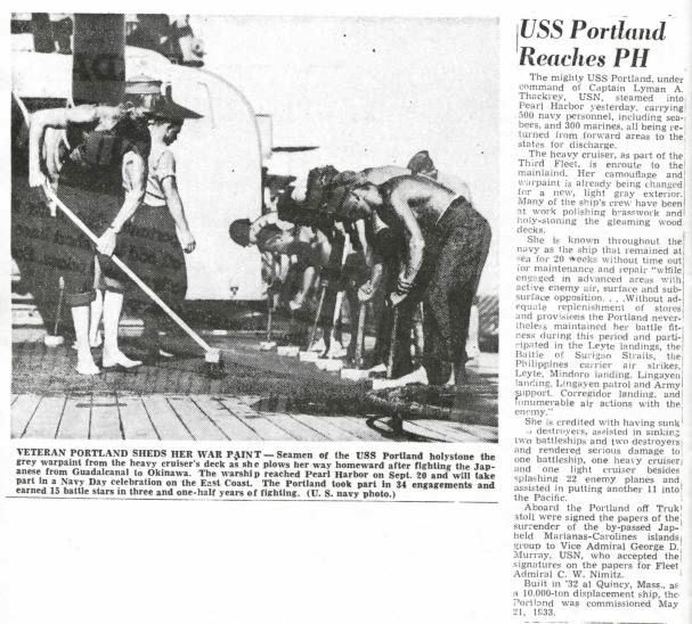

After Navy Day in Portland, Maine in 1945, we went to the Boston Navy Yard for repairs and modification. The planes were taken off, the two hangars cleaned out and 500 bunks were placed in each. We found out that we were to go to Le Havre, France to bring back soldiers. With about half the crew on leave or discharged, we were able to carry about 1,500 soldiers, and were to make the trip in 15 days.

While in Boston, I put in for driver, to take officers to town. It was on Thanksgiving Day that I took some officers over to the hotel and was to bring back the Captain's wife for dinner. Well, I had never been in Boston in my life. I got lost in the big city and was over an hour late getting back to the ship. Needless to say, that was my first and last driving duty.

On the way back from Le Havre, the ship was rocking and rolling. The waves were up to 100 feet high. We knew we were in a big storm. Some buddies and I were in the metal shop. We had a record player going and were drinking coffee when all of a sudden the water came in a port-hole seven feet off the deck. We had listed so the water ran down the passageway behind the hangar and on top of the record player.

Our shop had a metal half-door and we had it jammed shut. The water was running down the passageway about 6 inches deep. I saw souvenirs, cameras, blankets, clothes - going aft. I jumped over the half-door and went to check on the damage. I went forward and saw that the hangar door had caved in from the water pressure. Bunks were collapsed and damage was widespread.

I knew the area well, since my battle station was topside aft repair. I went back between the hangars where there was an up-take from the engine room. Other sailors and I saw a big hole in the screen. We looked in and saw a leg sticking out from under some blankets. John Siri and I jumped down there and got the body of a soldier out. Two had washed overboard from the quarterdeck.

We had a lot of repairs to do to the hangar doors and up forward in the port chain locker a seam had ruptured and the space was filling up. We had to pump out the locker. My helper, a ship fitter named McGill, and I took 4 x 4s and jacks to shore up the seam. I finally got a weld on it to hold. We were standing in water up to our knees and took some hard jolts from the electric welder.

The whole bow had lifted and twisted to the port about 2 feet. The deck in the officer's compartments was buckled very badly. Not many aboard knew all the damage that was done.

The Captain turned the ship south, toward the Azores Islands. When we got to the Azores we took off the dead and wounded. We were supposed to be back to New York Christmas Eve, but, because of the storm and detour, we didn't arrive until the 28th of December.

I was discharged from the ship in the first part of 1946 and thanks to the efforts of Lt., Barney Kliks, I received a commendation from Capt. Bibby for the work I had done during the storm.

Herman Ferguson Vol. II, pp. 127-128

After Navy Day in Portland, Maine in 1945, we went to the Boston Navy Yard for repairs and modification. The planes were taken off, the two hangars cleaned out and 500 bunks were placed in each. We found out that we were to go to Le Havre, France to bring back soldiers. With about half the crew on leave or discharged, we were able to carry about 1,500 soldiers, and were to make the trip in 15 days.

While in Boston, I put in for driver, to take officers to town. It was on Thanksgiving Day that I took some officers over to the hotel and was to bring back the Captain's wife for dinner. Well, I had never been in Boston in my life. I got lost in the big city and was over an hour late getting back to the ship. Needless to say, that was my first and last driving duty.

On the way back from Le Havre, the ship was rocking and rolling. The waves were up to 100 feet high. We knew we were in a big storm. Some buddies and I were in the metal shop. We had a record player going and were drinking coffee when all of a sudden the water came in a port-hole seven feet off the deck. We had listed so the water ran down the passageway behind the hangar and on top of the record player.

Our shop had a metal half-door and we had it jammed shut. The water was running down the passageway about 6 inches deep. I saw souvenirs, cameras, blankets, clothes - going aft. I jumped over the half-door and went to check on the damage. I went forward and saw that the hangar door had caved in from the water pressure. Bunks were collapsed and damage was widespread.

I knew the area well, since my battle station was topside aft repair. I went back between the hangars where there was an up-take from the engine room. Other sailors and I saw a big hole in the screen. We looked in and saw a leg sticking out from under some blankets. John Siri and I jumped down there and got the body of a soldier out. Two had washed overboard from the quarterdeck.

We had a lot of repairs to do to the hangar doors and up forward in the port chain locker a seam had ruptured and the space was filling up. We had to pump out the locker. My helper, a ship fitter named McGill, and I took 4 x 4s and jacks to shore up the seam. I finally got a weld on it to hold. We were standing in water up to our knees and took some hard jolts from the electric welder.

The whole bow had lifted and twisted to the port about 2 feet. The deck in the officer's compartments was buckled very badly. Not many aboard knew all the damage that was done.

The Captain turned the ship south, toward the Azores Islands. When we got to the Azores we took off the dead and wounded. We were supposed to be back to New York Christmas Eve, but, because of the storm and detour, we didn't arrive until the 28th of December.

I was discharged from the ship in the first part of 1946 and thanks to the efforts of Lt., Barney Kliks, I received a commendation from Capt. Bibby for the work I had done during the storm.

"STICK EM UP"

Bart Babcock

After the war, we had discharged many, many men, took the planes and the V division off and all the marine detachment. Those of us who were left (I was on a 6-year cruise beginning in June, 1940) had to stand some strange watches.

On our second trip across the Atlantic in December, 1945,1 had the Brig Watch, normally a Marine duty. The brig consisted of two cells with a short passageway between them, in the very stern of the, ship in F division quarters at the waterline. I relieved the watch, took the .45 and ejected the clip, pulled the slide back and looked through the barrel, let the slide go back, pulled the trigger and then reinserted the clip. I then settled back on a canvas stool and started reading "Our Navy."

The only prisoner was an AOL whom I had seen around the ship quite often. As I became engrossed in "Our Navy" I was jarred to hear a voice coming from the cell, within a few feet of my ear (my port ear.)

"Stick 'em up" the voice said. I turned and here was this prisoner pointing a Luger (one he had bought from a soldier on our first crossing) at me. I realized he was joking and told him "Put that thing away, or I'll take it from you."

You have probably wondered why we had Marines on the ship. Now you know.

Bart Babcock

After the war, we had discharged many, many men, took the planes and the V division off and all the marine detachment. Those of us who were left (I was on a 6-year cruise beginning in June, 1940) had to stand some strange watches.

On our second trip across the Atlantic in December, 1945,1 had the Brig Watch, normally a Marine duty. The brig consisted of two cells with a short passageway between them, in the very stern of the, ship in F division quarters at the waterline. I relieved the watch, took the .45 and ejected the clip, pulled the slide back and looked through the barrel, let the slide go back, pulled the trigger and then reinserted the clip. I then settled back on a canvas stool and started reading "Our Navy."

The only prisoner was an AOL whom I had seen around the ship quite often. As I became engrossed in "Our Navy" I was jarred to hear a voice coming from the cell, within a few feet of my ear (my port ear.)

"Stick 'em up" the voice said. I turned and here was this prisoner pointing a Luger (one he had bought from a soldier on our first crossing) at me. I realized he was joking and told him "Put that thing away, or I'll take it from you."

You have probably wondered why we had Marines on the ship. Now you know.

"I DON'T LIKE WATER"

Bob Ninberg Vol. II, pp. 124-125

On the last trip from Le Havre, France, some of the soldiers were from an all Black company of "big gun" men. They were the troops that stopped Rommel at the approach to Cairo. One was a sergeant with more stripes and hash marks than I had ever seen. He had taken up residence in #2 mess hall and every day when I walked past, he would yell "Hey, sonny, wake me when we hit rough weather."

After about the second day of the storm, I walked past him and said "I hope you're awake as it doesn't get much rougher than this." (Note - I think he was at least 3 shades paler.)

His reply blew me away: "Man, I've been in the army for six years, I have not seen my wife and kids, but if I make it back to land and get discharged, the very first thing I'm gonna do is head for a small lake about a mile from home. I left a row boat there and if it's still floating, I'm gonna take an axe and sink it. I don't ever want to go on water again and I might not even want to drink it."

Bob Ninberg Vol. II, pp. 124-125

On the last trip from Le Havre, France, some of the soldiers were from an all Black company of "big gun" men. They were the troops that stopped Rommel at the approach to Cairo. One was a sergeant with more stripes and hash marks than I had ever seen. He had taken up residence in #2 mess hall and every day when I walked past, he would yell "Hey, sonny, wake me when we hit rough weather."

After about the second day of the storm, I walked past him and said "I hope you're awake as it doesn't get much rougher than this." (Note - I think he was at least 3 shades paler.)

His reply blew me away: "Man, I've been in the army for six years, I have not seen my wife and kids, but if I make it back to land and get discharged, the very first thing I'm gonna do is head for a small lake about a mile from home. I left a row boat there and if it's still floating, I'm gonna take an axe and sink it. I don't ever want to go on water again and I might not even want to drink it."

ATLANTIC HURRICANE

(A letter home)

Barney Kliks Vol. II, pp. 125, 127

At sea

200 miles N.W. of

the Azores

19 Dec. 1945

Dear Folks,

I'm sending a copy of this to Peg, so you will both get the dope at the same time.

We are limping back to the Azores, as it is the closest land and Naval base.

First, I will not get home for Christmas, but am lucky as hell to be able to get home or back to the USA at all, and in one piece, so don't worry. I may not get to send you a telegram, as I suppose they do not want to make the news public until the official announcement by the Navy Dept and the next of kin are notified. I'll try to mail this from the Azores, hoping it reaches you before you have a chance to worry.

We rode out the worst storm the skipper and the old-time Navy men aboard this ship had ever been thru. For about 48 hours...maybe 50 or 60 we went through hell. You couldn't stand up, gear went flying around, chairs and tables piled up, our rooms were a mess, and water came in everywhere. We had been having terribly rough weather for several days as I wrote before to Peg, but then it got worse and worse, 'till we had 75 mile an hour winds, storm, huge waves higher than the ship. We had sprung a leak coming over and had temporarily caulked and welded it in Le Havre, but this time we had even greater troubles, and more dangerous ones. I will tell you all about it when I see you and after the Navy releases the details of the damage.

The night of the 17th and 18th was the worst, and I spent the entire night down below the water-tight doors and hatches helping the injured in sick bay and all the bunks around that vicinity where we stowed away the injured Peg will remember where that was. If we had gone down you wouldn't have had a prayer of getting out, so early in the game I took off my coat and life jacket and gave it to a wounded soldier who was worried, and suffered shock as well as other injuries and to whom it gave a lot of comfort. Besides, if I had worn a life belt, being healthy, and they being wounded wore none, it wouldn't have helped their morale any. My Boy Scout First Aid came in handy, and I directed stretcher bearers, got mattresses and bunks ready, rounded up 100 blankets which sailors freely gave up, took men into the operating room for treatment, led and helped carry them to bunks; cut off or tore off soaked clothing, dried them with clean towels, tucked them in to keep them warm and help with shock. I even learned how to give morphine serates (shots) and mark the patient with the amt. and hour. We had only 2 Navy and 2 Army (passenger) doctors (both sick) aboard and they more than had their hands full. I'll never forget that night as long as I live, and am sure glad I had something to keep me busy and was able to do some good. It would have been no time to be idle.

Well, I've had enuf of the N. Atlantic and enuf of storms at sea...almost worse that battle, for you can't fight back; can do nothing but hang on. I believe the Portland has made it's last trip, so might not have to go again. Hope so, anyway.

Love Barney

(A letter home)

Barney Kliks Vol. II, pp. 125, 127

At sea

200 miles N.W. of

the Azores

19 Dec. 1945

Dear Folks,

I'm sending a copy of this to Peg, so you will both get the dope at the same time.

We are limping back to the Azores, as it is the closest land and Naval base.

First, I will not get home for Christmas, but am lucky as hell to be able to get home or back to the USA at all, and in one piece, so don't worry. I may not get to send you a telegram, as I suppose they do not want to make the news public until the official announcement by the Navy Dept and the next of kin are notified. I'll try to mail this from the Azores, hoping it reaches you before you have a chance to worry.

We rode out the worst storm the skipper and the old-time Navy men aboard this ship had ever been thru. For about 48 hours...maybe 50 or 60 we went through hell. You couldn't stand up, gear went flying around, chairs and tables piled up, our rooms were a mess, and water came in everywhere. We had been having terribly rough weather for several days as I wrote before to Peg, but then it got worse and worse, 'till we had 75 mile an hour winds, storm, huge waves higher than the ship. We had sprung a leak coming over and had temporarily caulked and welded it in Le Havre, but this time we had even greater troubles, and more dangerous ones. I will tell you all about it when I see you and after the Navy releases the details of the damage.

The night of the 17th and 18th was the worst, and I spent the entire night down below the water-tight doors and hatches helping the injured in sick bay and all the bunks around that vicinity where we stowed away the injured Peg will remember where that was. If we had gone down you wouldn't have had a prayer of getting out, so early in the game I took off my coat and life jacket and gave it to a wounded soldier who was worried, and suffered shock as well as other injuries and to whom it gave a lot of comfort. Besides, if I had worn a life belt, being healthy, and they being wounded wore none, it wouldn't have helped their morale any. My Boy Scout First Aid came in handy, and I directed stretcher bearers, got mattresses and bunks ready, rounded up 100 blankets which sailors freely gave up, took men into the operating room for treatment, led and helped carry them to bunks; cut off or tore off soaked clothing, dried them with clean towels, tucked them in to keep them warm and help with shock. I even learned how to give morphine serates (shots) and mark the patient with the amt. and hour. We had only 2 Navy and 2 Army (passenger) doctors (both sick) aboard and they more than had their hands full. I'll never forget that night as long as I live, and am sure glad I had something to keep me busy and was able to do some good. It would have been no time to be idle.

Well, I've had enuf of the N. Atlantic and enuf of storms at sea...almost worse that battle, for you can't fight back; can do nothing but hang on. I believe the Portland has made it's last trip, so might not have to go again. Hope so, anyway.

Love Barney

LOST AT SEA

Ted Waller

It was during the first week of December, 1945 and the Portland was tied up at one of the piers in New York City. We had received notice that the ship was scheduled to make one or two trips to Le Havre, France, to pick up troops and bring them home. Half the crew was to be given 21 days leave and the remainder would make the trip to France.

George Pritchard, gunner's Mate 1/c in the 5th Division, and I were making a lot of our liberties together and, as luck would have it, we were in the group picked to stay in the States. As neither of us had ever been on an airplane before, we decided that it would be fun to fly to Chicago where I could visit my mother and George could run up to Michigan to see his family. I don't remember the name of the airline, but I will never forget that first flight on a DC-3 in midwinter.

When we returned to New York and reported in to the barracks on the pier where our crew was being housed, we were advised that the ship would be a few days late so we could have liberty any time we wanted to go ashore. A couple of hours later, George and I were in our favorite spot, the 32nd Street Bar and Grill, having a dinner and probably a few drinks. After a few more drinks, and not feeling the cold, we decided to take a walk up to Times Square and see the sights.

As you know, the New York Times building had a feature where late news flashes were displayed on a lighted sign that constantly changed. As we were walking up Broadway and looking at all of the lights and sights we noticed the news sign flash "USS PORTLAND LOST AT SEA!" We did not believe it at first so we stood there for about ten minutes until the message came around the next time. Needless to say this had a sobering effect in more ways than one. After reading this the second time, we rushed back to the pier where we were being housed and the message was confirmed by the Officer of the Deck.

It was not until the next morning that word was passed on the P. A. system that the Portland was not lost, but was severely damaged and had pulled in to the Azores for repairs. It was a great reunion when the Portland once again docked in New York City. After hearing some of the stories, we were glad to have missed this Portland cruise.

From the New York Daily News - Dec. 1945

"The heavy cruiser Portland - her forecastle buckled, her radar antenna smashed and her starboard hangar door ripped off - arrived in port yesterday after a week's delay which took a toll of two soldiers dead, one missing and fifty two injured.

"The battered vessel brought in 1,159 troops from Le Havre after being tossed about by two storms which the skipper. Captain L. H. Bibby, described as the worst in his 28 years at sea.

"The ship's navigator, Cdr. A. Jackson, said the wind indicator was broken at forty knots, but he felt sure the gales reached ninety miles an hour. Estimates on the mountainous waves reached as high as a hundred feet. Cdr. Jackson said he stood on the bridge, forty feet above the water line, and had to look up to see the crest of the waves.

"The two deaths and numerous injuries occurred Dec. 17 when one of the giant waves smashed the door to the starboard hangar, where 189 soldiers were bunked, and instantly created a scene of horror and confusion. Water rushed through the hangar "like a ten ton truck" said Cdr. Jackson, collapsing bunks and pinning many soldiers under the wreckage.

"Sgt. T. Lancian, of Everett, Mass., who was wounded at Bastogne, said the accident was more terrifying than his war experiences and "most of us thought the boat was sinking."

"A hero of the disaster was John Siri, 24 year old ship's cook first class, who broke three ribs while extricating two soldiers from the wreckage.

"Soldiers praised the quick action taken by the ship's crew in their rescue work and a speech made over the ship's loudspeaker by Capt. Bibby shortly after the tragedy occurred. At that time both soldiers and sailors were badly frightened and many believed that the ship 'was done for' said Cdr. Jackson, but the skipper's talk, "delivered in a calm, confident voice" explained to them what had happened and quieted their fears.

"The first storm occurred on the night of Dec. 16 when the winds were higher but the waves were not so large as on the following night when the second storm struck.

"On Dec. 18 the ship headed to the Azores because the boiler feed lines were clogged with salt water. At Ponte Delgada the Portland picked up boiler water and removed the 22 more seriously injured men, who were flown home in an Army C-54 plane.

"The ship remained in the Azores for four days and on the remainder of its voyage zigzagged to avoid the brunt of mountainous waves on her battered forecastle, the cruiser traveled about 1,000 extra miles on the ordinarily 3,000 mile trip and experienced only two calm days during the two weeks, one of them as she sailed up New York Harbor."

Ted Waller

It was during the first week of December, 1945 and the Portland was tied up at one of the piers in New York City. We had received notice that the ship was scheduled to make one or two trips to Le Havre, France, to pick up troops and bring them home. Half the crew was to be given 21 days leave and the remainder would make the trip to France.

George Pritchard, gunner's Mate 1/c in the 5th Division, and I were making a lot of our liberties together and, as luck would have it, we were in the group picked to stay in the States. As neither of us had ever been on an airplane before, we decided that it would be fun to fly to Chicago where I could visit my mother and George could run up to Michigan to see his family. I don't remember the name of the airline, but I will never forget that first flight on a DC-3 in midwinter.

When we returned to New York and reported in to the barracks on the pier where our crew was being housed, we were advised that the ship would be a few days late so we could have liberty any time we wanted to go ashore. A couple of hours later, George and I were in our favorite spot, the 32nd Street Bar and Grill, having a dinner and probably a few drinks. After a few more drinks, and not feeling the cold, we decided to take a walk up to Times Square and see the sights.

As you know, the New York Times building had a feature where late news flashes were displayed on a lighted sign that constantly changed. As we were walking up Broadway and looking at all of the lights and sights we noticed the news sign flash "USS PORTLAND LOST AT SEA!" We did not believe it at first so we stood there for about ten minutes until the message came around the next time. Needless to say this had a sobering effect in more ways than one. After reading this the second time, we rushed back to the pier where we were being housed and the message was confirmed by the Officer of the Deck.

It was not until the next morning that word was passed on the P. A. system that the Portland was not lost, but was severely damaged and had pulled in to the Azores for repairs. It was a great reunion when the Portland once again docked in New York City. After hearing some of the stories, we were glad to have missed this Portland cruise.

From the New York Daily News - Dec. 1945

"The heavy cruiser Portland - her forecastle buckled, her radar antenna smashed and her starboard hangar door ripped off - arrived in port yesterday after a week's delay which took a toll of two soldiers dead, one missing and fifty two injured.

"The battered vessel brought in 1,159 troops from Le Havre after being tossed about by two storms which the skipper. Captain L. H. Bibby, described as the worst in his 28 years at sea.

"The ship's navigator, Cdr. A. Jackson, said the wind indicator was broken at forty knots, but he felt sure the gales reached ninety miles an hour. Estimates on the mountainous waves reached as high as a hundred feet. Cdr. Jackson said he stood on the bridge, forty feet above the water line, and had to look up to see the crest of the waves.

"The two deaths and numerous injuries occurred Dec. 17 when one of the giant waves smashed the door to the starboard hangar, where 189 soldiers were bunked, and instantly created a scene of horror and confusion. Water rushed through the hangar "like a ten ton truck" said Cdr. Jackson, collapsing bunks and pinning many soldiers under the wreckage.

"Sgt. T. Lancian, of Everett, Mass., who was wounded at Bastogne, said the accident was more terrifying than his war experiences and "most of us thought the boat was sinking."

"A hero of the disaster was John Siri, 24 year old ship's cook first class, who broke three ribs while extricating two soldiers from the wreckage.

"Soldiers praised the quick action taken by the ship's crew in their rescue work and a speech made over the ship's loudspeaker by Capt. Bibby shortly after the tragedy occurred. At that time both soldiers and sailors were badly frightened and many believed that the ship 'was done for' said Cdr. Jackson, but the skipper's talk, "delivered in a calm, confident voice" explained to them what had happened and quieted their fears.

"The first storm occurred on the night of Dec. 16 when the winds were higher but the waves were not so large as on the following night when the second storm struck.

"On Dec. 18 the ship headed to the Azores because the boiler feed lines were clogged with salt water. At Ponte Delgada the Portland picked up boiler water and removed the 22 more seriously injured men, who were flown home in an Army C-54 plane.

"The ship remained in the Azores for four days and on the remainder of its voyage zigzagged to avoid the brunt of mountainous waves on her battered forecastle, the cruiser traveled about 1,000 extra miles on the ordinarily 3,000 mile trip and experienced only two calm days during the two weeks, one of them as she sailed up New York Harbor."

ATLANTIC HURRICANE - 1945

Ed Glatzel

On our second trip to Europe as a part of operation "Magic Carpet" bringing home troops from the European Theater of Operations, we encountered a terrific storm. At least two tremendous waves hit us resulting in serious damage and costing the lives of several soldiers. Part of the damage was to one of the hangars where some troops were bunked. The door was caved in, bunks smashed and many soldiers injured severely.

If you remember, the fireroom uptakes were located just inside the hangar doors on the inboard side between the two hangars. This was a big opening about 8' square which helped vent the firerooms. When the waves knocked down the hangar doors, the water kept coming in and went into the fireroom uptakes and flooded the firerooms.

Shipfitters were called to put a cover over the openings to keep the water out and electricians to lower submersible pumps down the opening to pump the water out. I was one of the electricians.

The pumps were big heavy steel, about 3' long and 10" in diameter. A heavy line was used to lower the pump down. It also had a heavy duty power cord to furnish current and a long hose for the water discharge. One man was guiding the hose down, one man was guiding the power line and a couple of men handled the pump.

About halfway down the men on the pump lines lowered away some but the man on the power line held fast, pulling the power lie clean out of the pump. The whole unit had to be pulled back up and taken down for service. It was fill of water where the line had pulled out so another pump had to be put in operation.

(ed. note.) Managing such an operation would have been difficult in calm weather. In the middle of a raging hurricane it took almost superhuman effort when just staying on your feet was almost impossible.

Ed Glatzel

On our second trip to Europe as a part of operation "Magic Carpet" bringing home troops from the European Theater of Operations, we encountered a terrific storm. At least two tremendous waves hit us resulting in serious damage and costing the lives of several soldiers. Part of the damage was to one of the hangars where some troops were bunked. The door was caved in, bunks smashed and many soldiers injured severely.

If you remember, the fireroom uptakes were located just inside the hangar doors on the inboard side between the two hangars. This was a big opening about 8' square which helped vent the firerooms. When the waves knocked down the hangar doors, the water kept coming in and went into the fireroom uptakes and flooded the firerooms.

Shipfitters were called to put a cover over the openings to keep the water out and electricians to lower submersible pumps down the opening to pump the water out. I was one of the electricians.

The pumps were big heavy steel, about 3' long and 10" in diameter. A heavy line was used to lower the pump down. It also had a heavy duty power cord to furnish current and a long hose for the water discharge. One man was guiding the hose down, one man was guiding the power line and a couple of men handled the pump.

About halfway down the men on the pump lines lowered away some but the man on the power line held fast, pulling the power lie clean out of the pump. The whole unit had to be pulled back up and taken down for service. It was fill of water where the line had pulled out so another pump had to be put in operation.

(ed. note.) Managing such an operation would have been difficult in calm weather. In the middle of a raging hurricane it took almost superhuman effort when just staying on your feet was almost impossible.

"SAFE" SAFE

Barney Kliks

On December 17, 1945 we were returning from Le Havre, France when we were hit by a storm carrying 90 knot winds and 100 foot waves. I was told that the huge safe in the communications shack had broken it s weld to the bulkhead and deck. It was pitching back and forth, threatening to ruin all of the equipment. I was ordered to take a sailor, don life jackets, carry a life line and hawser and secure the safe.

I got one of the radio men to help and the only access we had to the communications shack was up a couple of decks by a steel ladder out in the weather. It took us about an hour to get there as we could only make a step at a time whenever the ship made it to the center of its roll. We were badly beaten by the waves.

After securing the safe and sitting there resting, over the sound system came the order "All hands having experience in first aid, get down to sick bay on the double." We found our way back down to sick bay and were immediately put to work giving morphine to injured sailors and soldiers waiting to be treated by the doctors. A badly injured soldier tugged at my sleeve and said "Tell me lieutenant, are we going to sink?" I told him "Hell no – the Japs could not put us down and this storm is not going to, either." He then asked me why I was wearing a life jacket. After trying to explain why I was wearing it, I asked him if he would feel better if he had it. He assured me that he would.

Shortly after we got the soldiers quieted down in their wire litters, crammed down in that narrow passageway, we had another scare. The Damage Control boys started coming forward to shore up our damaged bow. They were carrying lumber, welding torches and wearing lanterns on their heads. That sight did little to make the injured soldiers happy.

One hero was a tough sergeant, with both legs crushed, a battered arm and strapped in his wire basket. He yelled at the complaining men - "Shut up. The Navy is doing all they can. Keep out of their way and hang on."

We had many unsung heroes from our crew - John Siri, ship's cook, who had three ribs broken while he rescued two soldiers trapped in the wreckage and Herman Ferguson, a Metalsmith in Damage Control. He did electric welding while standing knee deep in water, securing plates on the bow that had ruptured and was letting water in. He did it again by helping cut down the damaged and swinging hangar door. I helped write up a commendation for him.

I cannot remember what or how we ate during that week. The stoves were out and the labels had soaked off most of the canned goods.

When we finally made it to the Azores, we were all permitted to give the name and address of someone to notify. A one line telegram was sent to all those people. It only said that we had survived but this was important as the folks at home only knew that the Portland had not been heard from for several days and was “Lost at Sea.”

Barney Kliks

On December 17, 1945 we were returning from Le Havre, France when we were hit by a storm carrying 90 knot winds and 100 foot waves. I was told that the huge safe in the communications shack had broken it s weld to the bulkhead and deck. It was pitching back and forth, threatening to ruin all of the equipment. I was ordered to take a sailor, don life jackets, carry a life line and hawser and secure the safe.

I got one of the radio men to help and the only access we had to the communications shack was up a couple of decks by a steel ladder out in the weather. It took us about an hour to get there as we could only make a step at a time whenever the ship made it to the center of its roll. We were badly beaten by the waves.

After securing the safe and sitting there resting, over the sound system came the order "All hands having experience in first aid, get down to sick bay on the double." We found our way back down to sick bay and were immediately put to work giving morphine to injured sailors and soldiers waiting to be treated by the doctors. A badly injured soldier tugged at my sleeve and said "Tell me lieutenant, are we going to sink?" I told him "Hell no – the Japs could not put us down and this storm is not going to, either." He then asked me why I was wearing a life jacket. After trying to explain why I was wearing it, I asked him if he would feel better if he had it. He assured me that he would.